Culture in Medicine an Argument Against Competence Review

Abstract

Many medical accreditation bodies concord that medical students should be trained to care for various patient populations. Nevertheless, the teaching methods that medical schools employ to accomplish this goal vary widely. The purpose of this work is to summarize current cultural competency teaching for medical students and their evaluation methods. A scoping review was completed past searching the databases PubMed, Scopus, MedEdPORTAL, and MEDLINE for the search terms "medical instruction" and "cultural competency" or "cultural competence." Results were summarized using a narrative synthesis technique. Ane hundred fifty-four articles on cultural competency interventions for medical students were systematically identified from the literature and categorized by teaching methods, length of intervention, and content. Fifty-half-dozen articles had a full general focus, and ninety-eight articles were focused on specific populations including race/ethnicity, global health, socioeconomic status, language, clearing status, inability, spirituality at the end of life, rurality, and lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer. Nigh 54% of interventions used lectures as a pedagogy modality, 45% of the interventions described were mandatory, and ix.seven% of interventions were not formally evaluated. The authors advocate for expansion and more than rigorous analysis of teaching methods, education philosophies, and upshot evaluations with randomized controlled trials that compare the relative effectiveness of general and population-specific cultural competency interventions.

INTRODUCTION

Inquiry has shown that perceived sociocultural differences can affect communication and decision making and are directly linked to patient satisfaction, treatment plan adherence, and overall intendance quality.1,2,3,4 "Cultural competency" and "cultural humility" take emerged as approaches to addressing these differences in the healthcare organisation. Cultural competency has been defined as "a set up of congruent behaviors, attitudes, and policies that come together in a system, agency, or among professionals and enable… (providers) to work effectively in cross-cultural situations."5,6 Some fence that cultural competency is an unfeasible goal and that information technology is unrealistic to gear up this as a standard for health professionals. Others propose that providers should strive for cultural humility, a ready of skills focused on continuous learning and self-reflection on one's interactions with individuals from cultures different from their ain.7 As cultural competency is an older term and appears more than often in the literature, the authors apply this going forward, acknowledging that many institutions have embraced the term cultural humility.

Healthcare training institutions have the responsibleness to cultivate the compassion and humanism needed to produce well-rounded providers. The Liaison Committee on Medical Instruction (LCME) suggests that the medical curriculum should include teaching on the importance of developing strategies for addressing healthcare disparities, the principles of culturally competent care, and the ways in which culture affects a patient'southward experience of symptoms, illness, and treatment.8 Nearly accreditation bodies do not provide guidelines on how to accomplish this task, and as such, medical schools accept implemented a myriad of educational activity and assessment methods related to cultural competency and humility.viii,ix

Prior systematic reviews take examined curricula for healthcare professionals to analyze the affect of cultural competence preparation. Multiple studies have shown that cultural competency curricula positively inverse provider skills, knowledge, and attitudes. Beach et al.10 constitute that there was good evidence that cultural competency interventions improved patient satisfaction, merely limited testify that these interventions led to improvement in health outcomes. The current authors ready out to review the cultural competency literature and noticed a lack of studies outlining what topics medical schools were focusing on in their cultural competency interventions. Additionally, at that place was no standardized conceptual framework to categorize published interventions by length, educational activity approaches, or whether the intervention was required for graduation.

The authors' goal for this piece of work was to review the field of cultural competency curriculum for medical students and to categorize electric current published practices. The authors hope to identify gaps in the current literature such that medical educators are ameliorate equipped to develop deliberate curriculum focused on caring for diverse populations.

METHODS

A scoping review was completed by searching the databases PubMed, Scopus, MedEdPORTAL, and MEDLINE. The terms used in PubMed were "medical education" AND ("cultural competency" OR "cultural competence"), which yielded 490 articles. Scopus was searched using the terms "medical education" AND ("cultural competency" OR "cultural competence"), yielding 798 manufactures. MEDLINE was searched using the following: ("Education, Medical"[Mesh] OR "Education, Medical, Undergraduate"[Mesh]) AND "Cultural Competency"[Mesh], for a event of 358 manufactures. Every bit the term cultural humility is newer, it did not have its own MESH term and information technology was not included. Finally, MedEdPORTAL was searched using the term cultural competency which yielded 155 articles. This search resulted in 1801 total articles.

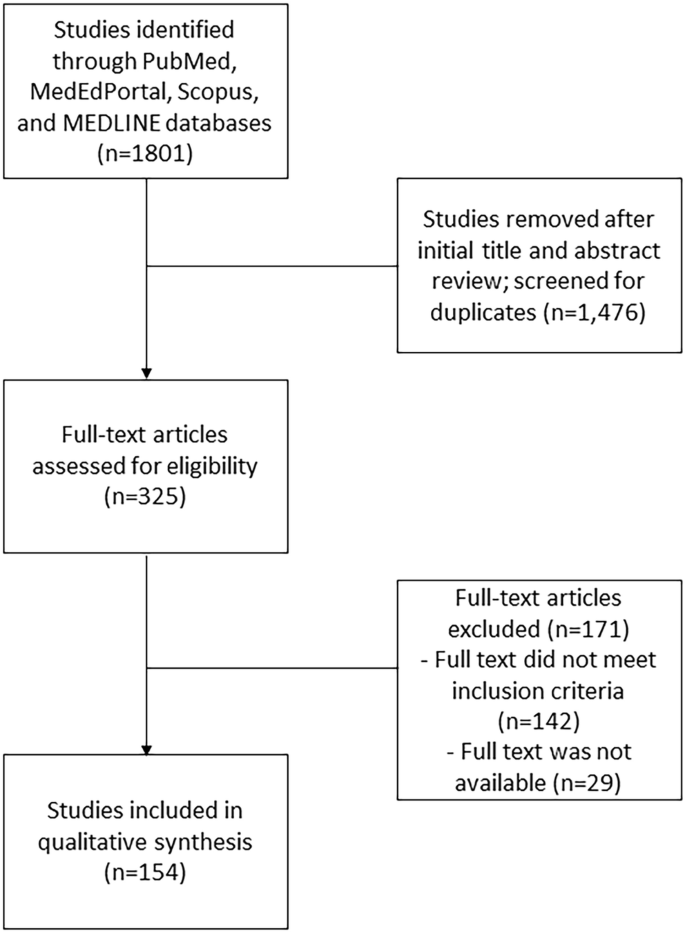

The resultant manufactures were considered eligible if they met the following criteria: (i) written in or translated into English; (two) published on or prior to December 31, 2017; (3) had full text accessible online for review; and (iv) described a specific cultural competency intervention targeted to medical students. To reduce selection bias, two reviewers independently reviewed the results from each database to make up one's mind the articles that met the inclusion and exclusion criteria (J.R.D. and F.F.). Whatsoever discrepancy was discussed with at least one other reviewer and resolved past majority opinion. Reviewers used the inclusion and exclusion criteria to review abstracts, by which 1476 manufactures were discarded. The remaining 325 articles were reviewed in their entirety. One hundred and seventy-one manufactures were excluded for non fulfilling the inclusion criteria, and of which, 29 manufactures were excluded since they did non have full text accessible for review. This resulted in 154 articles fulfilling criteria with total text available, which were included in the analysis of this literature review (Fig. 1).

Period diagram and results of literature review. Using PubMed, MedEdPORTAL, Scopus, and MEDLINE databases, 1801 articles were identified. During screening of titles and abstracts, 1476 were removed based on inclusion and exclusion criteria. One hundred and seventy-one manufactures were then excluded after full-text review because they did not meet criteria or the full text was not available. One hundred and fifty-four articles were included in final synthesis.

A modified narrative synthesis format for discussing results was chosen for the conceptual framework equally the articles varied in terms of research designs and data outcomes.xi,12 The stages of the narrative synthesis included the following: (one) developing the preliminary synthesis, (two) comparing themes within and between studies, and (3) thematic classification. The preliminary synthesis included extracting the following data: length of intervention, teaching methods, country of origin, effect mensurate, voluntariness of the intervention, type of intervention employed, and summary of chief study findings. Interventions were placed into five categories past length: 1–3 h, half day to 1 day, 1 mean solar day to 1 week, longer than 1 calendar week, and longitudinal throughout a year or entire curriculum. Interventions that did not have lengths mentioned were classified equally undetermined. 2 independent reviewers thematically categorized each study past area of focus (J.R.D. and F.F.). Finally, the authors resolved uncertainties in classification through give-and-take with multiple reviewers (K.East.J., F.F., J.R.D., J.T.). Studies that were especially innovative or broadly reflective of the category were highlighted. Equally many of the selected manufactures had disparate upshot measures, such as standardized patients' feedback, pre- and postal service-surveys, and focus groups, the efficacy of interventions was not compared.

RESULTS

Interventions Identified

One hundred fifty-4 unique manufactures fulfilled all inclusion criteria (Fig. 1). These were subsequently categorized past education methods, length of intervention, topics covered, outcome mensurate, and voluntariness of participation (Table 1). Topics identified were placed into two major categories, "Full general" and "Specific Population." Those in the "Specific Population" category were farther classified into categories including race/ethnicity, global health, rurality, socioeconomic status, language, refugee/asylum seekers, disability identities/deafened culture, religion/spirituality at the terminate of life, and Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer (LGBTQ). Virtually interventions utilized lectures to teach students (83/154). Discussion groups were some other popular pedagogy format (56/154). About interventions (64/154) were 1-h to 3-h events, and 45/154 of interventions were longitudinal. Most of the studies evaluated the intervention (139/154) with many using surveys (100/154) and knowledge-based tests (23/154).

Specific findings for each category are described in the following subsections. Interventions with interesting approaches in their education methods, evaluation, or content are as well included.

General

Fifty-six articles were classified as general, which included programs that provided frameworks for communicating with patients of various backgrounds, emphasized identifying i's ain bias, and/or focused on general principles for addressing sociocultural determinants of wellness.7,xiii,14,15,16,17,18,19,twenty,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,xxx,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,l,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,sixty,61,62,63,64,65,66 Of the 56 manufactures, 20 were 1–iii-h experiences, six were half 24-hour interval, 3 were between a day and a week, three were greater than i calendar week, 23 were longitudinal activities, and i article did non talk over program length. The most common instruction method was lecture (31/56), followed by discussion (26/56). Other popular education methods included written reflections (14/56), office-play (eleven/56), standardized patient encounters (10/56), and online modules (eight/56). Of the general interventions, 34 were required. Forty-four of the 56 interventions were evaluated: surveys were the most popular form of assay (34/56), cognition-based tests (5/56), standardized patient encounters (4/56), focus groups (ii/56), and interviews (ii/56).

In Betancourt and Cervantes, students learned to approach patients by assessing core cantankerous-cultural issues, exploring the significant of illness, determining social context, and engaging in negotiation. The authors stressed the importance of combining the knowledge of specific cultures with general communication skills that are applicable for diverse patient populations.17

Similarly, Dao et al.16 sought to avert the propagation of stereotypes by providing students with a general arroyo to patients of diverse backgrounds. Students were introduced to fundamental sociomedical themes to assist them understand the impact of these factors on patient care. Themes included socioeconomic grade, race, gender, LGBTQ issues, "compliance," the medical gaze, faith, and advocacy.16

Specific Populations

Ninety-eight articles were identified that described programs focused on a single population and the sociocultural factors that affect its members' wellness. These interventions were further subdivided into the following categories: race/ethnicity, global health, socioeconomic status, linguistic communication, refugee/asylum seekers, disability identities and deaf culture, spirituality at the end of life, rurality, and LGBTQ.

Race/Ethnicity

Xx articles identified interventions that addressed specific racial/ethnic populations without involving travel abroad.67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86 Seventeen of the twenty interventions were adult at US medical schools, while the remainder were from New Zealand, Canada, Australia, Romania, Federal republic of germany, and Russia. Ix articles focused on populations that were indigenous to the study'south state of origin. Seven of the interventions were ane–three h, 1 was half day, three were less than 1 calendar week, iv were integrated into clerkships, and 5 were longitudinal experiences. A multitude of teaching methods were employed including lecture (9/20), cultural immersion component (7/xx), online modules (6/20), and videos (iv/xx). 19 of the articles evaluated their programs with the bulk using surveys. All programs reported positive outcomes including comeback in students' attitudes and acquisition of skills to provide population-specific intendance.

I Canadian study used videos nigh the care of Chinese patients and showed that 67.3% of students had learned useful strategies to ameliorate serve immigrant patients.73 An overwhelming 79.6% of respondents stated that online videos could be an effective method in cultural competency training. Some other article compared two dissimilar types of online interventions: a module on interprofessional communication and a patient come across betwixt a educatee and a Salvadoran family.74 Students were evaluated through a standardized patient, and those who were exposed to the virtual patient module outperformed students who were not exposed to the module.

Global Health

15 articles were identified that focused on cultural competency development through global health experiences.87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101 14 of these described interventions with cultural immersion outside of one'southward dwelling country every bit the chief teaching method, with 9 of the 14 providing clinical experience. One intervention described a 3-h course preparing students to complete a global wellness plan.101 Eleven of the interventions were 1 month to a semester long, three were longitudinal, and one was 3 h. Additional instruction methods included written reflections (four/15), lectures (6/15), discussions (4/xv), online modules (1/15), and videos (1/xv). None of the international interventions were required for medical students. Nearly of the articles used surveys to clarify outcomes, although 3 also used interviews with students and two used a focus group. In those interventions that addressed outcomes, the bulk of students rated their program favorably.88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,100

In the study of Nishigori et al.,96 students participating in an substitution program between the UK and Japan noted that they developed a deeper understanding of dissimilar healthcare systems. Mao et al.94 reported that students taking an acupuncture and traditional Chinese medicine elective "increased their understanding of the challenges faced by immigrants who try to negotiate the complex healthcare organization."

Of note, 2 of the articles evaluated the furnishings of their programs with long-term follow-up. Hutchins et al.97 showed long-lasting furnishings in sometime participants of a I Health trip to Ecuador, especially regarding the use of Castilian language and cross-cultural skills. Jacobs et al.98 reported a similar outcome with participants in an commutation program from Germany to Federal democratic republic of ethiopia later on 8 years.

Socioeconomic Status

Half-dozen articles were identified specifically addressing issues affecting patients of low socioeconomic status (SES).102,103,104,105,106,107 5 of the interventions were extended clinical experiences, and one was 1–iii h. Four of the half dozen used lectures as a instruction modality, and 2 used a small group. Standardized Patient (SP) sessions, online modules, and written reflections were also used.

Turner and Farquhar102 used an interprofessional curricular program to help students place and understand the relationship betwixt health conditions and poverty and work to promote the welfare of people who are economically disadvantaged. Students who completed the intervention performed better than students of the prior year on standardized patient encounters and the USMLE Pace 2 Clinical Skills Exam.102

In the written report of Sheu et al.,104 students volunteered at student-run clinics targeting low-income populations. Participating students reported improved understanding only did not score differently on validated surveys of sociocultural attitudes when compared to students who did not participate.104

Language

13 articles focused on the language barriers affecting clinical care.108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116,117,118,119,120 5 of the interventions were longitudinal, seven of these interventions were one–3 h, and 1 was two and a one-half weeks. Eight out of the 13 interventions were mandatory. Almost all interventions included opportunities for students to practice their communication skills, whether through role-play, clinical experiences, online modules, or standardized patient encounters. 3 interventions likewise consisted of a lecture on working with interpreters. Most of the articles described positive results and good pupil reviews. Yet, i article found that almost twoscore% of students failed to use interpreters in an come across with a patient of limited English proficiency.111

Zanetti et al.115 described a iv-yr program that promotes cultural competency through civic engagement and 2nd language fluency. Students who participated reported greater conviction in obtaining a medical history in a dissimilar language, advocating for the healthcare needs of underserved populations, and assessing the wellness beliefs and do of patients from other cultures.115

Refugees or Asylum Seekers

Six manufactures which discussed interventions were aimed at populations of refugees or asylum seekers.121,122,123,124,125,126 One commodity described a i–3-h intervention, i was a full day, three were longitudinal, and 1 did not specify fourth dimension course. Well-nigh used lectures and clinical experiences as educational activity methods. Evaluation methods included surveys and essays. Asgary et al.121 taught students about asylum law through a serial of lectures, workshops, and clinical sessions. This intervention made employ of hands-on work preparing medical affidavits to assistance patients receive governmental services of which 89% were accepted in court. The students improved their attitudes toward aviary seekers, cognition of furnishings of torture, and efficacy in clinical evaluation.121

Disability Identities and Deaf Culture

10 manufactures were identified that addressed interventions related to disabilities, a concrete or mental impairment that limits the patient'due south daily activities.127,128,129,130,131,132,133,134,135,136 Only one of the manufactures described a longitudinal intervention with three of the 10 describing 1-h- to iii-h-long programs. The articles emphasized the importance of feel interacting with people with disabilities and developing a greater agreement of the bug they face when accessing healthcare. Nine of the interventions taught using lectures, two included standardized patient encounters, 3 used videos, one had an immersive experience, v used clinical experiences, and the terminal used role-play.

In the written report of Thew et al.,133 medical students attended a lecture and then a office reversal scenario, in which students attempted to communicate without speaking to deaf volunteers interim as providers. Students rotated through a doctor's office, a chemist's shop, and an emergency section and and then discussed their experiences in small-scale groups. This intervention was evaluated with surveys and institute comeback in the student's condolement interacting with deaf patients.133

Hagood et al.131 describes an elective class focusing on the transition from pediatric- to adult-centered care and the impact of chronic illness on independent functioning. Students reported that they appreciated the opportunity to interview caregivers and patients with cystic fibrosis.131

Spirituality and End of Life

Seven articles were identified that focused on issues of cultural competency related to religion and spirituality in the palliative intendance setting.137,138,139,140,141,142,143 6 of the interventions were i–iii-h experiences, and the concluding was during a 3rd-yr clerkship. All the interventions were voluntary. For instruction methods, three interventions used lectures, two used online modules, and 2 used role-play. To evaluate programme efficacy, two of the seven articles used cogitating essays, and three used surveys. The remaining manufactures used SP exams and knowledge-based tests.

Ane interdisciplinary intervention employed an online module for students from schools of medicine, social work, nursing, and chaplaincy. Through qualitative analysis of survey responses, the report concluded that students benefited from the program, but that medical students were less comfy addressing palliative intendance and religion than students from other programs. The authors propose that medical students might feel less confident because they have less feel with discussions about organized religion in their standard medical curriculum.142

Rurality

Three articles were identified that focused on rural populations, two from the USA and one from Australia.144,145,146 Ii of the three interventions were longitudinal, and the terminal was a week long. All interventions used immersion as a teaching method and were evaluated, using surveys in two interventions and an interview in the other. Daly et al.144 placed students in a clinical setting in a rural surface area for vi months. After this experience, the investigators conducted interviews with medical students, supervisors, and clinicians. Participants reported improved cultural sensation and personal/professional evolution and identified potential barriers to practicing in rural communities including academic isolation, geographical issues, and perceived education run a risk.144

LGBTQ

Xviii articles were identified as focusing on cultural competency training on gender and sexual minorities.147,148,149,150,151,152,153,154,155,156,157,158,159,160,161,162,163 Most of the interventions (16/eighteen) were designed as 1–3-h sessions, used lectures equally a teaching modality (8/18), and used surveys as an cess tool (15/18). SP sessions were too commonly used to teach and assess students' power to take an inclusive sexual history. Vanderleest and Galper147 depict a mandatory lecture-based intervention that educated 2d-yr students on terms including "transgender," "transsexual," and "transition." The lecture also taught students about how bigotry and bias contribute to transgender health disparities.147 In another SP session, students took a social history and discovered that the patient was questioning their sexual orientation and dealing with family unit pressures. Eighty-7 percent of students rated the session as good or excellent.150

DISCUSSION

Prior reviews have non focused on cultural competency training for medical students specifically and included providers at dissimilar levels of training and from unlike professions.10,164,165 This review focuses on medical students and is unique in that it identifies the primary teaching methods, lengths of interventions, topics covered, and evaluation methods used in published cultural competency interventions. Most interventions (54%) used lectures as a teaching modality, and 64% of the interventions were well-nigh specific populations. Most used some form of evaluation, with almost 65% using surveys to evaluate student improvement. Of note, about half of the programs were voluntary which introduces pick bias and tin can affect the educatee's self-perception of improvement.

As expected, lectures remain the predominant pedagogy modality in medical schoolhouse.166 It has become increasingly common for medical schools to expand their pedagogy to include non-traditional modalities such as team-based learning, standardized patients, and simulated patient experiences.166,167,168 As the curricular interventions for cultural competency training develop, medical schools should go on to move beyond lectures to encompass other didactics methods.

The use of calculator modules every bit a didactics modality was explored in several studies. Online modules and virtual patient interactions can exist ideal methods to provide students an opportunity to trial different advice techniques in a low-risk environment. However, no studies direct compare the effectiveness of virtual patients to standardized patient encounters representing a gap in the current medical education literature.

A dissever between the philosophies behind full general versus specific population-focused interventions became credible in reviewing the literature. Some authors argue that focusing on factual knowledge of a specific population increases the chance of promoting stereotypes and promotes the thought that one can gain complete understanding of another culture. These authors advocated for programs that focus on i'south ain biases and learning general strategies for cross-cultural advice.xvi The efficacy of interventions that focus on specific populations compared to those that employ a more general model should be evaluated through a randomized controlled trial.

In addition to formally comparing education styles, specific interventions should exist assessed in a standardized style. The Tool for Assessing Cultural Competence Preparation (TACCT) was developed by the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) to appraise the entire curriculum of an establishment. It does not, withal, assess skills gained from private interventions and their specific touch on on a student'due south knowledge and abilities.169 Furthermore, the TACCT was non designed to suggest teaching strategies. The development of a divide tool to examine educational goals and student outcomes from private interventions would exist a useful tool for more standardized evaluation of smaller components of curricula. Similarly, Gozu et al.164 found that about educators take limited admission to objective and standardized evaluation tools for cultural competence grooming interventions.

Strengths of this study include the number of papers reviewed, the description and analysis of the components of the interventions, and the inclusion of papers from different countries. However, there are several limitations in the nowadays review. First, this review is subject to publication bias, given that the authors are unable to speak to not-published interventions. Second, given the lack of direct comparisons between teaching methods and intervention types, the authors are unable to speak to relative effectiveness. Lastly, cultural competency equally both a scholarly concept and search term presents a limitation. Cultural competency as a MESH term may not capture all dimensions of culture and multifariousness.

CONCLUSIONS

The available literature describes a myriad of educational interventions for medical students that address the unique obstacles they may face when caring for patients of different backgrounds. The authors abet for further inquiry into non-traditional modalities, such equally depression-cost and easily disseminated online modules. Farther research should focus on developing standardized assessment tools for these interventions, equally well as randomized controlled trials to compare the relative effectiveness of general and population-specific cultural competency interventions.

References

-

Nelson A. Diff treatment: confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care. J Natl Med Assoc. 2002;94(8):666–668. https://doi.org/ten.1001/jama.290.eighteen.2487-b.

-

Stewart M, Chocolate-brown JB, Boon H, Galajda J, Meredith Fifty, Sangster M. Evidence on patient-doctor communication. Cancer Prev Command CPC = Prévention contrôle en cancérologie PCC. 1999;3(1):25–30. https://doi.org/x.1158/1940-6207.PREV-09-A25.

-

McLemore MR, Altman MR, Cooper Northward, Williams S, Rand 50, Franck L. Health care experiences of pregnant, birthing and postnatal women of color at risk for preterm birth. Soc Sci Med. 2018;201:127–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scog.2018.05.001.

-

De Marco Yard, Thorburn South, Zhao W. Perceived discrimination during prenatal care, labor, and delivery: An examination of data from the Oregon pregnancy risk assessment monitoring system, 1998-1999, 2000, and 2001. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(10):1818–1821. https://doi.org/ten.2105/AJPH.2007.123687.

-

Cantankerous TL, Bazron BJ, Dennis KW, Isaacs MR, Benjamin MP. Towards a culturally competent intendance; A monograph on effective services for minority children who are severely emotionally disturbed. Child Adolesc Serv Syst Progr. 1989:ninety. https://doi.org/10.1109/55.877196.

-

Education USM. Cultural Competency Training Treating Patients from Different Cultures. Med Educ. 2005;11(December):290–294. https://doi.org/ten.1007/s11116-009-9222-z.

-

Carter MM, Lewis EL, Sbrocco T, et al. Cultural competency training for third-year clerkship students: furnishings of an interactive workshop on student attitudes. J Natl Med Assoc. 2006;98(eleven):1772–1778.

-

Committee L on ME. Functions and Structure of a Medical School. 2017.

-

Australian Medical Council. Review of the Standards for Assessment and Accreditation of Primary Medical Programs by the Australian Medical Council. 2017.

-

Beach MC, Toll EG, Gary TL, et al. Cultural competence: a systematic review of health care provider educational interventions. Med Care. 2005;43(4):356–373.

-

Popay J, Roberts H, Sowden A, et al. Guidance on the Conduct of Narrative Synthesis in Systematic Reviews. Vol METHODS BR.; 2006. https://doi.org/ten.1111/j.1523-536x.1995tb00261.x.

-

Leamy M, Bird V, Le Boutillier C, Williams J, Slade M. Conceptual framework for personal recovery in mental health: Systematic review and narrative synthesis. Br J Psychiatry. 2011;199(6):445–452. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.110.083733.

-

Ewart, Barry; Sandars J. Community involvement in undergraduate medical education. Clin Teach. 3(3):148–153.

-

Parisi V, Ahmed Z, Lardner D, Cho Eastward. Global wellness simulations yield culturally competent medical providers. Med Educ. 2012;46(11):1126–1127. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.12012.

-

Kulkarni A, Francis ER, Clark T, Goodsmith Northward, Fein O. How we developed a locally focused Global Health Clinical Preceptorship at Weill Cornell Medical College. Med Teach. 2014:1–5. https://doi.org/x.3109/0142159X.2014.886764.

-

Dao DiK, Goss AL, Hoekzema Every bit, et al. Integrating Theory, Content, and Method to Foster Disquisitional Consciousness in Medical Students: A Comprehensive Model for Cultural Competence Grooming. Acad Med. 2017;92(3):335–344. https://doi.org/x.1097/ACM.0000000000001390.

-

J.R. B, Chiliad.C. C. Cross-Cultural Medical Instruction in the The states: Fundamental Principles and Experiences. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2009;25(nine):471–478. https://doi.org/x.1016/S1607-551X(09)70553-4.

-

Kutob RM, Bormanis J, Crago M, Gordon P, Shisslak CM. Using standardized patients to teach cross-cultural communication skills. Med Teach. 2012;34(7):594. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2012.675101.

-

Beck BWMBTBSYSAS. Evolution, Implementation and Evaluation of an M3 Customs Wellness Curriculum. Med Educ Online. 2004;ix(1).

-

Crandall SJ, George 1000, Marion GS, Davis S. Applying theory to the design of cultural competency preparation for medical students: a case study. Acad Med. 2003;78(six):588–594. https://doi.org/x.1097/00001888-200306000-00007.

-

Crosson JC, Deng W, Brazeau C, Boyd L, Soto-Greene M. Evaluating the Effect of Cultural Competency Training on Medical Student Attitudes. Fam Med. 2004;36(iii):199–203.

-

Swanberg SM, Abuelroos D, Dabaja Due east, et al. Partnership for Variety: A Multidisciplinary Approach to Nurturing Cultural Competence at an Emerging Medical School. Med Ref Serv Q. 2015;34(four):451–460. https://doi.org/10.1080/02763869.2015.1082379.

-

Jarris YS, Bartleman A, Hall EC, Lopez L. A preclinical medical pupil curriculum to innovate health disparities and cultivate culturally responsive intendance. J Natl Med Assoc. 2012;104(9–10):404–411. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0027-9684(15)30193-0.

-

Miller East, Light-green AR. Educatee reflections on learning cross-cultural skills through a "cultural competence" OSCE. Med Teach. 2007;29(four). https://doi.org/ten.1080/01421590701266701.

-

Ho MJ, Gaufberg E, Huang WJ. Problem-based learning: Hidden curricular messages and cultural competence. Med Educ. 2008;42(11):1122–1123. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.2008.03211.x.

-

Kaul P, Guiton K. Responding to the challenges of pedagogy cultural competency. Med Educ. 2010;44(5):506. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.2010.03691.x.

-

Lee AL, Mader EM, Morley CP. Teaching cantankerous-cultural communication skills online: A multi-method evaluation. Fam Med. 2015;47(4):302–308.

-

Hawthorne Thou, Prout H, Kinnersley P, Houston H. Evaluation of different commitment modes of an interactive e-learning programme for education cultural diverseness. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;74(i):5–11. https://doi.org/ten.1016/j.pec.2008.07.056.

-

Whitford DL, Hubail AR. Cultural sensitivity or professional acculturation in early clinical experience? Med Teach. 2014;36(11):951–957. https://doi.org/x.3109/0142159X.2014.910296.

-

Genao I, Bussey-Jones J, St. George DM, Corbie-Smith G. Empowering students with cultural competence cognition: Randomized controlled trial of a cultural competence curriculum for third-year medical students. J Natl Med Assoc. 2009;101(12):1241–1246. https://doi.org/x.1016/S0027-9684(15)31135-4.

-

Bertelsen NS, DallaPiazza M, Hopkins MA, Ogedegbe Grand. Teaching global health with simulations and case discussions in a medical educatee selective. Global Health. 2015;11(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12992-015-0111-2.

-

Clementz L, McNamara M, Burt NM, Sparks M, Singh MK. Starting with Lucy: Focusing on Human Similarities Rather Than Differences to Address Health Care Disparities. Acad Med. 2017;92(9):1259–1263. https://doi.org/ten.1097/ACM.0000000000001631.

-

Carpenter R, Estrada CA, Medrano Chiliad, Smith A, Stanford Massie F. A Web-Based Cultural Competency Training for Medical Students: A Randomized Trial. Am J Med Sci. 2015;349(5):442–446. https://doi.org/x.1097/MAJ.0000000000000351.

-

Hsieh JG, Hsu M, Wang YW. An anthropological approach to teach and evaluate cultural competence in medical students—The application of mini-ethnography in medical history taking. Med Educ Online. 2016;21(1). https://doi.org/10.3402/meo.v21.32561.

-

Addy CL, Browne T, Blake EW, Bailey J. Enhancing interprofessional educational activity: Integrating public wellness and social piece of work perspectives. Am J Public Wellness. 2015;105:S106–S108. https://doi.org/x.2105/AJPH.2014.302502.

-

Ivory Yard, Bandler L, Hawke C, Armstrong B. A clinical approach to population medicine. Clin Teach. 2013;10(ii):94–98. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1743-498X.2012.00618.x.

-

Shields HM, Nambudiri VE, Leffler DA, et al. Using Medical Students to Enhance Curricular Integration of Cross-Cultural Content. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2009;25(9):493–502. https://doi.org/ten.1016/S1607-551X(09)70556-X.

-

Shellenberger S, Dent MM, Davis-Smith K, Seale JP, Weintraut R, Wright T. Cultural Genogram: A Tool for Pedagogy and Exercise. Fam Syst Heal. 2007;25(iv):367–381. https://doi.org/ten.1037/1091-7527.25.4.367.

-

Primack BA, Bui T, Fertman CI. Social marketing meets wellness literacy: Innovative improvement of wellness intendance providers' comfort with patient interaction. Patient Educ Couns. 2007;68(1):3–ix. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2007.02.009.

-

Ogur B, Hirsh D, Krupat Eastward, Bor D. The Harvard Medical School-Cambridge Integrated Clerkship: An innovative model of clinical education. Acad Med. 2007;82(four):397–404. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e31803338f0.

-

Wilkinson JE. Utilise of a writing elective to teach cultural competency and professionalism. Fam Med. 2006;38(10):702–704.

-

Carrillo JE, Greenish AR, Betancourt JR. Cross-cultural principal care: A patient-based approach. Ann Intern Med. 1999;130(10):829–834. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-130-10-199905180-00017.

-

Singh Southward, Barua P, Dhaliwal U, Singh North. Harnessing the medical humanities for experiential learning. Indian J Med Ethics. 2017;2(3):147–152. https://doi.org/10.20529/IJME.2017.050.

-

Saypol B, Drossman DA, Schmulson MJ, et al. A review of iii educational projects using interactive theater to improve dr.-patient communication when treating patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Rev Esp Enfermedades Dig. 2015;107(v):268–273. https://www.scopus.com/inwards/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-84945245409&partnerID=40&md5=7d124ba7ca3b733f041a6ee735f2303a.

-

Elnashar M, Abdelrahim H, Fetters Physician. Cultural competence springs up in the desert: The story of the middle for cultural competence in wellness care at Weill Cornell Medical College in Qatar. Acad Med. 2012;87(6):759–766. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e318253d6c6.

-

Knipper M, Seeleman IC, Essink ML. How should indigenous diversity be represented in medical curricula? A plea for systematic grooming in cultural competence. Tijdschrift voor Medisch Onderwijs. 2010:i–seven.

-

Thompson BM, Haidet P, Casanova R, et al. Medical students' perceptions of their teachers' and their own cultural competency: implications for teaching. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25 Suppl 2(Suppl 2):S91–four. https://doi.org/ten.1007/s11606-009-1245-9.

-

Lypson ML, Ross PT, Kumagai AK. Medical students' perspectives on a multicultural curriculum. J Natl Med Assoc. 2008;100(9):1078–1083. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0027-9684(15)31448-half dozen.

-

McDonald M, W J, Israel T. From Identification to Advancement: A Module for Teaching Social Determinants of Wellness. MedEdPORTAL Publ. 2015. https://doi.org/10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10266.

-

Kodjo C, Lee B, Morgan A, et al. Twist on Cultural Sensitivity. MedEdPORTAL Publ. 2014. https://doi.org/10.15766/mep_2374-8265.9931.

-

Stuart Eastward, Bereknyei S, Long M, Blankenburg R, Weak V, Garcia R. Standardized Patient Cases for Skill Edifice in Patient-centered, Cantankerous-cultural Interviewing (Stanford Gap Cases). MedEdPORTAL Publ. 2014. https://doi.org/10.15766/mep_2374-8265.9133.

-

Fredrick Northward. Teaching Social Determinants of Health Through Mini-Service Learning Experiences. MedEdPORTAL Publ. 2014. https://doi.org/10.15766/mep_2374-8265.9056.

-

Elliott D, George C, Signorelli D, Trial J. Stereotypes and Bias at the Psychiatric Bedside—Cultural Competence in the Third Year Required Clerkships. MedEdPORTAL Publ. 2014. https://doi.org/x.15766/mep_2374-8265.1150.

-

Elson M. Cultural Sensitivity in OB/GYN: the Ultimate Patient-Centered Care. MedEdPORTAL Publ. 2014. https://doi.org/10.15766/mep_2374-8265.1658.

-

DeGannes C, Woodson Coke Yard, Sanders-Phillips Yard, Henderson T. A Minor-Group Reflection Exercise for Increasing the Awareness of Cultural Stereotypes: A Facilitator'south Guide. MedEdPORTAL Publ. 2014. https://doi.org/ten.15766/mep_2374-8265.668.

-

Kobylarz F, Heath J, Similar R, Granville 50. The ETHNICS Mnemonic: Clinical Tool, Didactics, and Small Group Facilitator's Guide. MedEdPORTAL Publ. 2014. https://doi.org/ten.15766/mep_2374-8265.600.

-

Bower D, Webb T, Larson G, et al. Patient Centered Care Workshop: Providing Quality Health Care to a Diverse Population. MedEdPORTAL Publ. 2014. https://doi.org/10.15766/mep_2374-8265.579.

-

Crandall South. Constituent Class in Culture and Diversity. MedEdPORTAL Publ. 2014. https://doi.org/ten.15766/mep_2374-8265.192.

-

Elliott D, Schaff P, Woehrle T, Walsh A, Trial J. Narrative Reflection in Family unit Medicine Clerkship—Cultural Competence in the 3rd Twelvemonth Required Clerkships. MedEdPORTAL Publ. 2014. https://doi.org/10.15766/mep_2374-8265.1153.

-

Kutscher E, Boutin-Foster C. Customs Perspectives in Medicine: Elective for Showtime-Yr Medical Students. MedEdPORTAL Publ. 2016;122. https://doi.org/10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10501.

-

Gill A, Thompson B, Teal C, et al. Best Intentions: Using the Implicit Associations Test to Promote Reflection About Personal Bias. MedEdPORTAL Publ. 2014. https://doi.org/10.15766/mep_2374-8265.7792.

-

Lypson M, Perlman R, Silveria M, Lash R, Johnson C. The Social History…Information technology'southward About the Patient—Culture and All. MedEdPORTAL Publ. 2014. https://doi.org/10.15766/mep_2374-8265.3149.

-

Elliott D. Cultural Self Awareness Workshop. MedEdPORTAL Publ. 2014. https://doi.org/10.15766/mep_2374-8265.1128.

-

Blueish A. Cultural Competency Interviewing Instance Using the ETHNIC Mnemonic. MedEdPORTAL Publ. 2014. https://doi.org/10.15766/mep_2374-8265.155.

-

Drake C, Keeport Thousand, Chapman A, Chakraborti C. Social Contexts in Medicine: A Patient-Centered Curriculum Empowering Medical Students to Provide Contextualized Intendance. MedEdPORTAL Publ. 2017;13. https://doi.org/x.15766/mep_2374-8265.10541.

-

Bereknyei S, Foran S, Scott A, Braddock C, Johnson K, Miller T. Stopping Bigotry Earlier it Starts: The Touch on of Civil Rights Laws on Healthcare Disparities—A Medical School Curriculum. MedEdPORTAL Publ. 2014. https://doi.org/10.15766/mep_2374-8265.7740.

-

Allwardt D. Culturally Competent Health Care Practise with Older Adults. MedEdPORTAL Publ. 2014. https://doi.org/10.15766/mep_2374-8265.254.

-

Martinez I, Ilangovan K, Whisenant Due east, Pedoussaut One thousand, Lage O. Breast Health Disparities: A Primer for Medical Students. MedEdPORTAL Publ. 2016;12. https://doi.org/x.15766/mep_2374-8265.10471.

-

Hafner C. Introduction to Traditional Chinese Medicine (Out of Print). MedEdPORTAL Publ. 2014. https://doi.org/ten.15766/mep_2374-8265.221.

-

Denson One thousand. Virtual Patient Instance #4: Mrs. Violetta Mitsuko Tang—Principal Diagnosis: Osteoporosis/Incontinence. MedEdPORTAL Publ. 2014. https://doi.org/10.15766/mep_2374-8265.136.

-

Whitney Ann Cesari, William F. Brescia PhD, Kabir Harricharan Singh, Adeleke Oni, Anureet Cheema, Catherine Coffman, Aaron Creek, Crisanto Torres, Marissa Mencio, Stacy Clayton, Carmen Weaver JW. Medical Spanish. MedEdPORTAL Publ. 2012;8(9171).

-

Muntean V, Calinici T, Tigan S, Fors UGH. Language, culture and international commutation of virtual patients. BMC Med Educ. 2013;13(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6920-13-21.

-

Zhang C, Cho K, Chu J, Yang J. Bridging the gap: Enhancing cultural competence of medical students through online videos. J Immigr Small Heal. 2014;16(2):326–327. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-012-9755-7.

-

Kron FW, Fetters MD, Scerbo MW, et al. Using a calculator simulation for teaching advice skills: A blinded multisite mixed methods randomized controlled trial. Patient Educ Couns. 2017;100(four):748–759. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2016.10.024.

-

Mihalic AP, Morrow JB, Long RB, Dobbie AE. A validated cultural competence curriculum for US pediatric clerkships. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;79(1):77–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2009.07.029.

-

Lee WWVJN. Medical School Hotline: Promoting Diversity of the Health Intendance Workforce. Hawaii Med J. 2010;5(ane):130–131.

-

Sopoaga F, Zaharic T, Kokaua J, Covello S. Grooming a medical workforce to meet the needs of various minority communities. BMC Med Educ. 2017;17(i). https://doi.org/ten.1186/s12909-017-0858-seven.

-

Mak DB, Miflin B. Living and working with the people of "the bush-league": A foundation for rural and remote clinical placements in undergraduate medical didactics. Med Teach. 2012;34(9). https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2012.670326.

-

Morell VW, Sharp PC, Crandall SJ. Creating student awareness to improve cultural competence: creating the disquisitional incident. Med Teach. 2002;24(5):532–534. https://doi.org/x.1080/0142159021000012577.

-

Pinnock R, Jones R, Wearn A. Learning and assessing cultural competence in paediatrics. Med Educ. 2008;42(eleven):1124–1125. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.2008.03213.x.

-

Hudson GL, Maar M. Faculty analysis of distributed medical educational activity in Northern Canadian Ancient communities. Rural Remote Health. 2014;14(four).

-

Huria T, Palmer S, Beckert L, Lacey C, Pitama Due south. Indigenous wellness: Designing a clinical orientation programme valued by learners. BMC Med Educ. 2017;17(one). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-017-1019-eight.

-

Smith JD, Wolfe C, Springer South, et al. Using cultural immersion equally the platform for teaching Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health in an undergraduate medical curriculum. Rural Remote Health. 2015;fifteen(3):3144.

-

Carpenter D-AL, Kamaka ML, Kaulukukui CM. An innovative approach to developing a cultural competency curriculum; efforts at the John A. Burns School of Medicine, Department of Native Hawaiian Health. Hawaii Med J. 2011;lxx(11 Suppl 2):xv–19. http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=mnh&AN=22235152&site=ehost-live.

-

Kumagai AK, Kakwan Yard, Sediqe South, Dimagno MM. Actors' personal stories in example-based multicultural medical education. Med Educ. 2010;44(5):506–507. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.2010.03672.x.

-

Topping D. An interprofessional instruction Russian cultural competence form: Implementation and follow-upward perspectives. J Interprof Intendance. 2015;29(five):501–503. https://doi.org/10.3109/13561820.2015.1012582.

-

Ziganshin BA, Yausheva LM, Sadigh M, et al. Training Immature Russian Physicians in Republic of uganda: A Unique Program for Introducing Global Wellness Pedagogy in Russia. Ann Glob Heal. 2015;81(5):627–635. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aogh.2015.10.007.

-

Bruno DM, Imperato PJ. A Global Wellness Constituent for U.s.a. Medical Students: The 35 Year Feel of the State Academy of New York, Downstate Medical Center, School of Public Health. J Community Wellness. 2015;forty(2):187–198. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-014-9981-0.

-

Jordan J, Hoffman R, Arora One thousand, Coates W. Activated learning; providing structure in global health educational activity at the David Geffen School of Medicine at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA)—a airplane pilot study. BMC Med Educ. 2016;16(1):63. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-016-0581-9.

-

Allison J, Mulay S, Kidd M. Life in unexpected places: Employing visual thinking strategies in global health grooming. Educ Heal Chang Learn Pract. 2017;30(i):64–67. https://doi.org/10.4103/1357-6283.210511.

-

Green SS, Comer L, Elliott Fifty, Neubrander J. EXPLORING the Value of an International Service-Learning EXPERIENCE in Honduras. Nurs Educ Perspect. 2011;32(5):302–307. https://doi.org/10.5480/1536-5026-32.five.302.

-

Godkin M, Savageau J. The effect of medical students' international experiences on attitudes toward serving underserved multicultural populations. Fam Med. 2003;35(four):273–278.

-

Godkin MA, Savageau JA. The issue of a global multiculturalism track on cultural competence of preclinical medical students. Fam Med. 2001;33(3):178–186.

-

Mao JJ, Wax J, Barg FK, Margo K, Walrath D. A gain in cultural competence through an international acupuncture constituent. Fam Med. 2007;39(1):16–xviii.

-

Knipper Yard, Baumann A, Hofstetter C, Korte R, Krawinkel M. Internationalizing Medical Education: The Special Rail Curriculum "Global Health" at Justus Liebig University Giessen. GMS Zeitschrift für medizinische Ausbildung. 2015;32(5):Doc52. https://doi.org/10.3205/zma000994.

-

Nishigori H, Otani T, Plint S, Uchino M, Ban N. I came, I saw, I reflected: A qualitative study into learning outcomes of international electives for Japanese and British medical students. Med Teach. 2009;31(5). https://doi.org/10.1080/01421590802516764.

-

Hutchins FT, Chocolate-brown LD, Poulsen KP. An anthropological arroyo to teaching health sciences students cultural competency in a field school program. Acad Med. 2014;89(2):251–256. https://doi.org/ten.1097/ACM.0000000000000088.

-

Jacobs F, Stegmann K, Siebeck 1000. Promoting medical competencies through international exchange programs: Benefits on communication and effective medico-patient relationships. BMC Med Educ. 2014;14(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6920-14-43.

-

John C, Asquith H, Wren T, Mercuri South, Brownlow S. A student-led global health education initiative: Reflections on the Kenyan village medical teaching program. J Public health Res. 2016;five(1):7–9. https://doi.org/10.4081/jphr.2016.646.

-

Holmes D, Zayas LE, Koyfman A. Student objectives and learning experiences in a global wellness constituent. J Community Health. 2012;37(v):927–934. https://doi.org/x.1007/s10900-012-9547-y.

-

Lee P, Johnson A, Rajashekara Due south, et al. Clinical Topics in Global Wellness: A Practical Introduction for Pre-Clinical Medical Students. MedEdPORTAL Publ. 2014. https://doi.org/x.15766/mep_2374-8265.9471.

-

Turner JL, Farquhar 50. One medical school's effort to set the workforce for the time to come: Preparing medical students to intendance for populations who are publicly insured. Acad Med. 2008;83(7):632–638. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e31817836af.

-

Smith-Campbell B. Health professional person students' cultural competence and attitudes toward the poor: The influence of a clinical practicum supported by the national wellness service corps. J Allied Health. 2005;34(1):56–62.

-

Sheu L, Lai CJ, Coelho AD, et al. Impact of Student-Run Clinics on Preclinical Sociocultural and Interprofessional Attitudes: A Prospective Accomplice Analysis. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2012;23(3):1058–1072. https://doi.org/10.1353/hpu.2012.0101.

-

Bullock K, Jackson BR, Lee J. Engaging communities to enhance and strengthen medical instruction: Rationale and summary of feel. World Med Heal Policy. 2014;6(2):133–141. https://doi.org/ten.1002/wmh3.94.

-

Wong JW. Medical Schoolhouse Hotline: Cultural Competency in Serving the Homeless in Hawai'i at the John A. Burns Schoolhouse of Medicine. Hawaii J Med Public Health. 2016;75(1):18–21.

-

Pickrell J, Spector G, Chi D, Riedy C. Working Together to Access Dental Care for Immature Underserved Children: A Problem-Based Learning Approach to Increase Wellness Professional Students Sensation. MedEdPORTAL Publ. 2014. https://doi.org/10.15766/mep_2374-8265.9380.

-

Lie D, Bereknyei S, Braddock CH, Encinas J, Ahearn S, Boker JR. Assessing medical students' skills in working with interpreters during patient encounters: A validation study of the interpreter calibration. Acad Med. 2009;84(5):643–650. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e31819faec8.

-

Azam S, Carroll Thou. Enhancing students' communication in an ethnic language. Med Educ. 2013;47(eleven):1144–1145. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.12345.

-

Xiao W, Chen X, Chen M, Liao R. Developing cross-cultural competence in Chinese medical students. Med Teach. 2013;35(9):788–789. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2013.786178.

-

Fung CC, Lagha RR, Henderson P, Gomez AG. Working with interpreters: how student behavior affects quality of patient interaction when using interpreters. Med Educ Online. 2010;15. https://doi.org/ten.3402/meo.v15i0.5151.

-

Lie D, Boker J, Bereknyei S, Ahearn S, Fesko C, Lenahan P. Validating measures of tertiary yr medical students' use of interpreters past standardized patients and faculty observers. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(SUPPL. two):336–340. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-007-0349-3.

-

Lie DA, Bereknyei Due south, Vega CP. Longitudinal development of medical students' communication skills in interpreted encounters. Educ Heal Chang Learn Pract. 2010;23(3):466. https://login.ezproxy.net.ucf.edu/login?auth=shibb&url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=cmedm&AN=21290365&site=ehost-live%5Cnhttps://login.ezproxy.cyberspace.ucf.edu/login?auth=shibb&url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?directly=true&db=.

-

McEvoy M, Santos MT, Marzan M, Dark-green EH, Milan FB. Teaching medical students how to use interpreters: a three year experience. Med Educ Online. 2009;14:12. https://doi.org/10.3885/meo.2009.Res00309.

-

Zanetti ML, Godkin MA, Twomey JP, Pugnaire MP. Global longitudinal pathway: Has medical pedagogy curriculum influenced medical students' skills and attitudes toward culturally various populations? Teach Learn Med. 2011;23(3):223–230. https://doi.org/x.1080/10401334.2011.586913.

-

Nora LM, Daugherty SR, Mattis-Peterson a, Stevenson L, Goodman LJ. Improving cross-cultural skills of medical students through medical schoolhouse-community partnerships. Westward J Med. 1994;161(two):144–147.

-

Dawson A, Patti B. Castilian Acquisition Begets Enhanced Service (S.A.B.E.South.): A Starting time-Level Medical Castilian Curriculum. MedEdPORTAL Publ. 2014. https://doi.org/10.15766/mep_2374-8265.9057.

-

Trial J, Elliott D, Lauzon V, Lie D, Chvira E Interpretation at the OB/GYN Bedside—Cultural Competence in the Third Year Clerkships. MedEdPORTAL Publ. 2014. https://doi.org/ten.15766/mep_2374-8265.1148.

-

Waldman S, Kalet A. Working With Interpreters: Learning To Acquit A Cross-Language Medical Interview With An Online Web-Based Module (Out of Print). MedEdPORTAL Publ. 2014. https://doi.org/x.15766/mep_2374-8265.654.

-

Lie D. Interpreter Cases for Cultural Competency Teaching. MedEdPORTAL Publ. 2014. https://doi.org/10.15766/mep_2374-8265.205.

-

Asgary R, Saenger P, Jophlin L, Burnett DC. Domestic Global Health: A Curriculum Instruction Medical Students to Evaluate Refugee Aviary Seekers and Torture Survivors. Teach Acquire Med. 2013;25(4):348–357. https://doi.org/x.1080/10401334.2013.827980.

-

Knipper Thou, Akinci Southward, Soydan Due north. Culture and healthcare in medical education: migrants' health and beyond. GMS Z Med Ausbild. 2010;27(3):Doc41. https://doi.org/10.3205/zma000678.

-

Albritton TA, Wagner PJ. Linking Cultural Competency and Community Service: A Partnership between Students, Kinesthesia, and the Community. Acad Med. 2002;77(7):738–739. https://doi.org/x.1097/00001888-200207000-00024.

-

Griswold Grand, Kernan JB, Servoss TJ, Saad FG, Wagner CM, Zayas LE. Refugees and medical pupil training: Results of a programme in primary care. Med Educ. 2006;40(vii):697–703. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2929.2006.02514.x.

-

Stone H, Choi R, Aagaard E, et al. Refugee Health Elective. MedEdPORTAL Publ. 2014. https://doi.org/10.15766/mep_2374-8265.9457.

-

DeFries T, Rodrigues M, Ghorob A, Handley M. Health Communication and Action Planning with Immigrant Patients: Aligning Clinician and Community Perspectives. MedEdPORTAL Publ. 2015. https://doi.org/10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10050.

-

Woodard LJ, Havercamp SM, Zwygart KK, Perkins EA. An innovative clerkship module focused on patients with disabilities. Acad Med. 2012;87(4):537–542. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e318248ed0a.

-

Jain Dr. Southward, Foster E, Biery N, Boyle 5. Patients with disabilities every bit teachers. Fam Med. 2013;45(1):37–39.

-

Rossignol L. Relationship between Participation in Patient- and Family-Centered Care Training and Communication Adaptability among Medical Students: Changing Hearts, Changing Minds. Perm J. 2015. https://doi.org/ten.7812/TPP/14-110.

-

Eddey GE, Robey KL. Considering the civilisation of disability in cultural competence teaching. Acad Med. 2005;fourscore(7):706–712. https://doi.org/x.1097/00001888-200507000-00019.

-

Hagood JS, Lenker C V, Thrasher S. A grade on the transition to adult care of patients with childhood-onset chronic illnesses. Acad Med. 2005;80(four):352–355. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-200504000-00009.

-

Hoang L, LaHousse SF, Nakaji MC, Sadler GR. Assessing deaf cultural competency of physicians and medical students. In: Journal of Cancer Pedagogy. Vol 26. 2011:175–182. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13187-010-0144-four.

-

Thew D, Smith SR, Chang C, Starr M. The deaf strong infirmary program: a model of diversity and inclusion preparation for first-year medical students. Acad Med. 2012;87(11):1496–1500. https://doi.org/x.1097/ACM.0b013e31826d322d.

-

Lapinski J, Colonna C, Sexton P, Richard Thousand. American Sign Linguistic communication and Deaf Civilisation Competency of Osteopathic Medical Students. Am Ann Deaf. 2015;160(1):36–47. https://doi.org/ten.1353/aad.2015.0014.

-

Bradford North, Mulroy B. Medical Students every bit Coaches in Transitions of Care for Youth with Special Wellness Care Needs. MedEdPORTAL Publ. 2015. https://doi.org/10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10183.

-

Rogers J, Morris M, Hook C, Havyer R. Introduction to Inability and Health for Preclinical Medical Students: Didactic and Inability Panel Discussion. MedEdPORTAL Publ. 2016;12. https://doi.org/ten.15766/mep_2374-8265.10429.

-

Stoller Fifty, Fowler K. Spiritual Histories: Putting Religio-Cultural Competence into Practice. MedEdPORTAL Publ. 2015. https://doi.org/10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10029.

-

Stoller Fifty, Blanchard E, Fowler K. Trigger Topics: Where Religion & Wellness Intendance Intersect. MedEdPORTAL Publ. 2015. https://doi.org/10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10007.

-

Spike J, Rousso J. Starchild Cherrix: Negotiating almost Religious Beliefs and Complementary and Alternative Medicine. MedEdPORTAL Publ. 2014. https://doi.org/ten.15766/mep_2374-8265.3164.

-

Leonard B. Spirituality in Healthcare (Out of Print). MedEdPORTAL Publ. 2014. https://doi.org/ten.15766/mep_2374-8265.208.

-

Lubimir KT, Wen AB. Towards cultural competency in cease-of-life communication training. Hawaii Med J. 2011;70(11):239–241. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=3215988&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract.

-

Ellman MS, Schulman-Dark-green D, Blatt Fifty, et al. Using Online Learning and Interactive Simulation To Teach Spiritual and Cultural Aspects of Palliative Care to Interprofessional Students. J Palliat Med. 2012;15(11):1240–1247. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2012.0038.

-

Tater-Shigematsu S, Grainger-Monsen M. The impact of film in teaching cultural medicine. Fam Med. 2010;42(3):170–172.

-

Daly Chiliad, Perkins D, Kumar K, Roberts C, Moore M. What factors in rural and remote extended clinical placements may contribute to preparedness for practice from the perspective of students and clinicians? Med Teach. 2013;35(11):900–907. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2013.820274.

-

Brumby SA, Ruldolphi J, Rohlman D, Donham KJ. Translating agricultural wellness and medicine education across the Pacific: A U.s. and Australian comparing study. Rural Remote Health. 2017;17(1). https://doi.org/10.22605/RRH3931.

-

Keys III R, Desnick L, Bienz D, Evans D. Public Health Community Externship. MedEdPORTAL Publ. 2015. https://doi.org/10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10260.

-

Vanderleest JG, Galper CQ. Improving the Health of Transgender People: Transgender Medical Didactics in Arizona. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2009;20(5):411–416. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jana.2009.07.003.

-

Neff A, Kingery Southward. Consummate Androgen Insensitivity Syndrome: A Problem-Based Learning Case. MedEdPORTAL Publ. 2016;12. https://doi.org/ten.15766/mep_2374-8265.10522.

-

Jin H, Dasgupta S. Genetics in LGB Assisted Reproduction: Two Flipped Classroom, Progressive Disclosure Cases. MedEdPORTAL Publ. 2017;13. https://doi.org/10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10607.

-

Curren C, Thompson L, Altneu E, Tartaglia K, Davis J. Nathan/Natalie Marquez: A Standardized Patient Case to Innovate Unique Needs of an LGBT patient. MedEdPORTAL Publ. 2015. https://doi.org/10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10300.

-

Gallego J, Knudsen J. LGBTQI* Divers: An Introduction to Understanding and Caring for the Queer Community. MedEdPORTAL Publ. 2015. https://doi.org/ten.15766/mep_2374-8265.10189.

-

Gelman A, Amin P, Pletcher J, Fulmer 5, Kukic A, Spagnoletti C. A Standardized Patient Example: A Teen Questioning His/Her Sexuality is Bullied at Schoolhouse. MedEdPORTAL Publ. 2014. https://doi.org/10.15766/mep_2374-8265.9876.

-

Mehringer J, Salary E, Cizek South, Kanters A, Fennimore T. Preparing Future Physicians to Care for LGBT Patients: A Medical School Curriculum. MedEdPORTAL Publ. 2014. https://doi.org/10.15766/mep_2374-8265.9342.

-

Sullivan Westward, Eckstrand K, Blitz C, Peebles K, Lomis K, Fleming A. An Intervention for Clinical Medical Students on LGBTI Health. MedEdPORTAL Publ. 2014. https://doi.org/10.15766/mep_2374-8265.9349.

-

Croft C, Pletcher J, Fulmer 5, Steele R, Solar day H, Spagnoletti C. A Same-Sex Couple Copes with Stop-of-Life Problems: A Case Materials Guide. MedEdPORTAL Publ. 2014. https://doi.org/10.15766/mep_2374-8265.9438.

-

Sell J, George D, Levine G. HIV: A Socioecological Case Written report. MedEdPORTAL Publ. 2016;12. https://doi.org/x.15766/mep_2374-8265.10509.

-

Leslie K, Steinbock Southward, Simpson R, Jones VF, Sawning S. Interprofessional LGBT Health Equity Education for Early Learners. MedEdPORTAL Publ. 2017;13. https://doi.org/10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10551.

-

Gacita A, Gargus E, Uchida T, et al. Introduction to Safe Space Training: Interactive Module for Promoting a Safe Infinite Learning Environment for LGBT Medical Students. MedEdPORTAL Publ. 2017;13. https://doi.org/ten.15766/mep_2374-8265.10597.

-

Calzo J, Melchiono M, Richmond T, et al. Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Adolescent Health: An Interprofessional Instance Word. MedEdPORTAL Publ. 2017;13. https://doi.org/10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10615.

-

Potter Fifty, Burnett-Bowie S-A, Potter J. Teaching Medical Students How to Ask Patients Questions Virtually Identity, Intersectionality, and Resilience. MedEdPORTAL Publ. 2016;12. https://doi.org/10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10422.

-

Bakhai Due north, Shields R, Barone K, Sanders R, Fields E. An Active Learning Module Education Advanced Advice Skills to Care for Sexual Minority Youth in Clinical Medical Teaching. MedEdPORTAL Publ. 2016;12. https://doi.org/10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10449.

-

Bakhai N, Ramos J, Gorfinkle N, et al. Introductory Learning of Inclusive Sexual History Taking: An East-Lecture, Standardized Patient Case, and Facilitated Debrief. MedEdPORTAL Publ. 2016;12. https://doi.org/x.15766/mep_2374-8265.10520.

-

Lee R, Loeb D, Butterfield A. Sexual History Taking Curriculum: Lecture and Standardized Patient Cases. MedEdPORTAL Publ. 2014;10. https://doi.org/10.15766/mep_2374-8265.9856.

-

Gozu A, Embankment MC, Price EG, et al. Self-administered instruments to measure cultural competence of health professionals: A systematic review. Teach Learn Med. 2007;19(two):180–190. https://doi.org/x.1080/10401330701333654.

-

Price EG, Embankment MC, Gary TL, et al. A systematic review of the methodological rigor of studies evaluating cultural competence preparation of health professionals. Acad Med. 2005;80(6):578–586. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-200506000-00013.

-

Zinski A, Blackwell KTCPW, Belue FM, Brooks WS. Is lecture dead? A preliminary report of medical students' evaluation of teaching methods in the preclinical curriculum. Int J Med Educ. 2017;8:326–333. https://doi.org/10.5116/ijme.59b9.5f40.

-

Graffam B. Agile learning in medical education: Strategies for beginning implementation. Med Teach. 2007;29(ane):38–42. https://doi.org/ten.1080/01421590601176398.

-

Barrows HS. Problem-based learning in medicine and beyond: A brief overview. New Dir Teach Larn. 1996;1996(68):iii–12. https://doi.org/ten.1002/tl.37219966804.

-

Jernigan VBB, Tran 1000, Norris KC. An Examination of Cultural Competence Training in U.s. Medical Educational activity Guided by the Tool for Assessing Cultural Competence Training. J Heal Disparities Res Pract J Heal Disparities Res Pract J Heal Disparities Res Pract. 2016;9(3):150–167. https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt.3121.ChIP-nexus.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the Office of Variety Programs at Washington University School of Medicine for their support during the evolution of this manuscript. The authors would also like to admit the contributions of the Medical Educational activity Enquiry Unit at the Office of Medical Student Education at Washington University School of Medicine.

Author information

Affiliations

Contributions

JRD, FFF, KEJ, JT, DC, and WRR all made equal and significant contributions to this manuscript's formulation and design and to the assay and estimation, drafted and revised the manuscript critically for intellectual content, and approved the concluding version for publication. All authors agree to be held responsible for all aspects of the work.

Respective author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do non have a conflict of involvement.

Additional data

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Near this article

Cite this article

Deliz, J.R., Fears, F.F., Jones, 1000.E. et al. Cultural Competency Interventions During Medical Schoolhouse: a Scoping Review and Narrative Synthesis. J GEN INTERN MED 35, 568–577 (2020). https://doi.org/ten.1007/s11606-019-05417-5

-

Received:

-

Revised:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

Result Date:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-05417-5

KEY WORDS

- cultural competence

- cultural humility

- culture

- medical education

- diversity

Source: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11606-019-05417-5

0 Response to "Culture in Medicine an Argument Against Competence Review"

Post a Comment